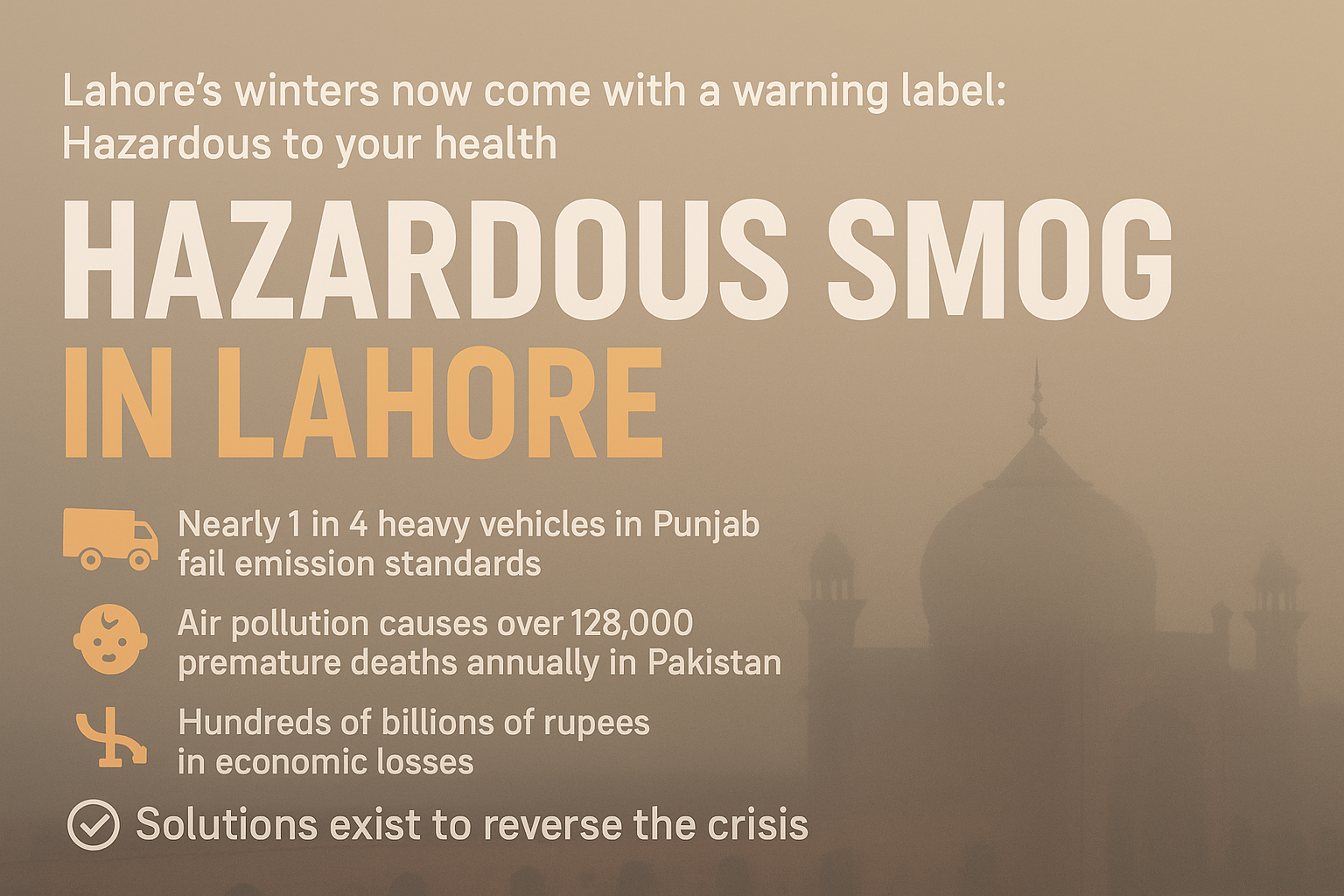

Punjab’s Smog Crisis Explained: The Numbers, the Damage, and a 3-Tier Action Plan

Each winter, the skies of Punjab turn a suffocating shade of grey. Medid creates hype “smog in Lahore.’ Cities such as Lahore, Faisalabad, and Gujranwala now rank among the most polluted in the world—recording air quality indices (AQI) well above 400 on bad days, levels classified as “hazardous.” The phenomenon, colloquially known as smog season, has become an annual crisis. What was once dismissed as a seasonal inconvenience is now a full-blown public health emergency—and an economic one too.

Recent enforcement drives by the Pakistan Environmental Protection Agency (Pak-EPA) in Islamabad revealed that nearly 20–27 percent of heavy vehicles tested failed the National Environmental Quality Standards (NEQS) for emissions. Similar campaigns in Punjab have found comparable or worse results. The culprits are familiar: old diesel trucks, buses, and long-haul trailers spewing thick plumes of black smoke. These are not isolated offenders but symptoms of a deeply systemic failure in emissions control, regulation, and institutional accountability.

Smog in Lahore: The Health and Economic Burden

The consequences are stark. Pakistan is estimated to suffer over 128,000 premature deaths annually attributable to air pollution, most linked to particulate matter (PM₂.₅ and PM₁₀). Children and the elderly bear the brunt, facing heightened risks of asthma, bronchitis, cardiovascular disease, and reduced cognitive performance. Economically, the damage is staggering: lower productivity, higher healthcare costs, and the erosion of human capital.

A valuation study by the Lahore School of Economics quantified the environmental costs of automobile emissions—including PM10, NOx, SO₂, and CO—as running into hundreds of billions of rupees annually. Put simply, the cost of inaction is far greater than the investment required for remedial measures.

Lahore’s 2019 ambient PM₂.₅ concentration—measured at roughly 123 µg/m³, or 24 times the World Health Organization guideline—illustrates how Pakistan’s air pollution (and smog in Lahore) crisis has transcended environmental boundaries to become a public-health and fiscal issue. The irony is that most of these emissions are preventable through better regulation, maintenance, and technological upgrades.

Why Vehicles Matter

The transport sector contributes between 5 percent and over 70 percent of urban air pollution in Pakistan, depending on the city and estimation method. This wide range reflects poor data quality and the lack of continuous emission inventories, but the trend is unmistakable. A 2023 emissions inventory for Lahore found that the average Pakistani vehicle emits 3.6 times more nitrogen oxides and 25 times more carbon per kilometre than a typical vehicle in a developed country.

These numbers are not just an engineering failure—they are an institutional one. The outdated Motor Vehicle Rules (1969) and patchy enforcement of fitness certification mean that unfit vehicles continue to operate unchecked. Fuel adulteration further worsens combustion inefficiency, while inspection and maintenance regimes remain sporadic and often compromised by corruption or lack of capacity.

Smog in Lahore Punjab, therefore, is not just a meteorological event amplified by crop burning; it is a by-product of cumulative neglect across transport, fuel, and regulatory systems.

Accountability and Institutional Gaps

Emissions control requires a chain of accountability that begins at policy design and extends through enforcement. Yet, in Pakistan, environmental agencies operate under resource and jurisdictional constraints. While the Pak-EPA and provincial EPAs occasionally launch inspection drives, these remain reactive, not preventive.

More troubling is the lack of harmonisation between vehicle-inspection standards and NEQS parameters. Motor vehicle examiners often use outdated opacity meters, while private certification centres lack standardisation. Enforcement, too, is inconsistent—fines are nominal, rarely collected, and insufficient to deter violators. Without institutional reform, the system perpetuates itself: polluting vehicles remain on the road because enforcement is sporadic and weak.

The Economics of Clean Air

Economists often argue that environmental degradation (like smog in Lahore) is not a “free” externality—it carries measurable costs. For Pakistan, these include lost workdays, hospital expenditures, reduced agricultural productivity (due to ozone and particulate deposition), and declining urban livability.

Investing in clean air is not a luxury but a form of preventive economic policy. The National Clean Air Policy (2023) offers a broad framework, but implementation must be localised and sequenced. For example, short-run measures can yield rapid dividends in Punjab’s smog belt if aligned with proper monitoring and incentives.

A Three-Tier Action Plan

Immediate (0–6 months):

- Emergency enforcement drives in Lahore, Faisalabad, and Gujranwala targeting high-emitting diesel vehicles, with mobile testing units and roadside penalties linked to vehicle registration databases (key to control smog in Lahore)

- Ban on fuel adulteration through joint raids by OGRA and provincial EPAs; simultaneous public campaigns on vehicle maintenance.

- Public health advisory systems using real-time AQI alerts, school closures, and distribution of N95 masks during high-smog days.

Short-Run (6–24 months):

- Upgrade vehicle inspection and maintenance (I/M) systems across Punjab, harmonising standards with NEQS, and digitising certification to reduce corruption. Implement it in Lahore first to manage smog in Lahore.

- Fleet renewal incentives—for example, tax rebates or low-interest financing for replacing vehicles older than 15 years.

- Adoption of Euro-IV or higher fuel standards nationwide to cut sulfur content in diesel and petrol.

- Pilot low-emission zones in Lahore’s central districts to discourage entry of high-emission vehicles.

Medium-Term (2–5 years):

- Transition to cleaner transport technologies—public investment in electric buses and hybrid freight vehicles through public-private partnerships.

- Institutional reform: strengthen provincial EPAs with autonomous budgets, digital monitoring tools, and independent audit powers.

- Integrated urban air-quality management—linking emissions control with land-use planning, waste management, and industrial zoning.

- Public accountability framework: annual publication of emissions compliance data, enforcement statistics, and health-impact metrics to sustain public pressure.

Conclusion

Smog in Lahore Punjab is not an act of nature; it is a man-made crisis that reflects decades of neglect and fragmented governance. But it is also reversible. Cleaner air is not just an environmental goal—it is an economic imperative tied to productivity, health, and fiscal sustainability.

The haze that shrouds Lahore each winter is both literal and metaphorical—a veil over institutional inertia. Lifting it will demand not just cleaner fuels and newer vehicles, but cleaner governance. The time for rhetoric has long passed; the cost of inaction is already written in the air we breathe.

Leave a Reply