Breaking Pakistan’s Debt Trap: Global Lessons for Reform 2025

By: Dr. Ghulam Mohey-ud-din

Pakistan’s economy has long been stuck in a familiar loop, the famous ‘Pakistan’s Debt Trap’. Each crisis sends officials back to the International Monetary Fund (IMF) in search of another lifeline. Terms are hammered out, bailouts are released, promises of reform are made—and then forgotten.

According to Reuters, Pakistan has signed more than twenty IMF programs since the late 1950s and now owes the Fund more than six billion dollars. An Atlantic Council study estimates that public and publicly guaranteed debt sits at roughly three quarters of gross domestic product, ranking Pakistan among the most indebted of its peers. For many Pakistanis, these numbers are not mere abstractions. They translate into chronic austerity, deteriorating public services, and the ever-present fear of collapse.

1. Pakistan’s Debt Trap: A Recurring Dilemma

Successive governments have made the same pledges: widen the tax base, fix the energy sector, privatize loss-making state companies, and improve governance. Yet those promises rarely outlast their headlines.

-

Narrow tax base: Reliant on salaried workers, formal businesses, and import duties, while much of the economy remains informal.

-

Energy sector woes: Theft, untargeted subsidies, and poor billing systems fuel a ballooning circular debt—rising from 227 billion rupees in 2013 to over 2.3 trillion by 2021.

-

Stalled privatization: Despite selling 172 enterprises between 1991 and 2015, more than 200 state-owned firms remain, many loss-making.

-

Political dysfunction: Frequent government changes and military interventions weaken reform consistency.

At the heart of these failures lies poor governance, elite capture, and an overemphasis on short-term fixes rather than structural transformation.

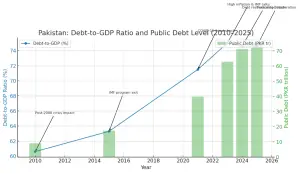

Over the past decade, Pakistan’s public debt has grown sharply—both in absolute PKR terms and as a share of national output. From around 9 trillion PKR in 2010 (with a debt-to-GDP of ~ 60 %) to over 62 trillion PKR by 2023 (debt-to-GDP ~ 75 %), the burden has ballooned. State Bank of Pakistan+3Wikipedia+3Macrotrends+3

By 2024, public debt reportedly reached Rs 74 trillion, pushing debt-to-GDP to levels earlier unseen. Pkrevenue.com+3Economy.pk+3SAMAA TV+3

Projections for 2025 suggest a moderation in the debt-to-GDP ratio (~ 74.6 %), but not because of debt reduction—rather because stronger GDP growth is expected to absorb some of the burden. Trading Economics

The visual clearly shows how public debt is not just rising—it’s becoming an increasingly larger share of national output, constraining fiscal flexibility and heightening risk.

2. Structural Weaknesses in the Domestic Economy

Beyond Pakistan’s debt trap numbers, deeper economic flaws perpetuate Pakistan’s vulnerability:

-

Weak revenue system: Tax exemptions for elites and resistance to consumption tax reforms leave fiscal policy unbalanced.

-

Energy bottlenecks: Instead of investing in renewables or grid upgrades, resources are diverted to plugging deficits.

-

Public enterprise inefficiency: Political interference erodes the effectiveness of privatization.

-

Skewed spending priorities: High defense allocations crowd out much-needed investment in education and healthcare.

These internal weaknesses make externally designed IMF reforms less effective, since they assume greater state capacity and political will than exists.

3. Lessons from Vietnam: Sequenced and Gradual Reform

Vietnam’s trajectory offers an outstanding example of patient reform to manage debt trap. Emerging from war and isolation in the 1980s, Hanoi avoided shock therapy. Instead:

-

Agricultural reform: Farmers retained surplus production, raising rural incomes and freeing labor for industry.

-

Enterprise autonomy: State-owned firms gained independence before facing competition.

-

Gradual liberalization: Trade reforms and WTO accession came only after domestic adjustments had stabilized.

-

Long-term investment focus: Attracting stable export-oriented FDI, particularly in manufacturing.

By 2023, foreign-owned firms accounted for three quarters of Vietnam’s exports, transforming living standards. The lesson: reforms succeed when paced appropriately and rooted in comparative advantages. This offers a useful insights for management of Pakistan’s debt trap.

4. Bangladesh’s Experience: Inclusive and Labor-Intensive Growth

Bangladesh’s rise demonstrates how simple, locally tailored strategies can generate outsized results and managing debt trap.

-

Garments boom: Duty-free input access, credit facilities, and support for female workers built a $47 billion export sector (84% of exports).

-

Remittances: Diaspora inflows supported consumption and investment.

-

Microfinance innovation: Institutions like Grameen Bank extended credit to millions, especially women, with repayment rates over 98%.

These policies were not just economic—they empowered women socially and politically, reshaping Bangladesh’s development trajectory.

5. Ethiopia’s Path: Infrastructure-Led Development

Ethiopia shows another model: leveraging public investment to lay foundations for growth.

-

Infrastructure first: Roads, hydropower, telecoms, and water systems expanded access.

-

Social gains: Between 2004 and 2016, almost 60 million gained safe water, household electrification doubled, and vaccination rates rose sharply.

-

Debt challenges: Borrowing raised concerns, but the investments created capacity for future enterprise.

Ethiopia proves that debt-financed development can work if investments are strategic and inclusive.

6. Charting a Way Forward for Pakistan

Drawing from these experiences, Pakistan’s pathway must combine fiscal responsibility with developmental vision:

-

Strengthen tax capacity: Digital tools, broadened base (agriculture, real estate), reduced reliance on regressive indirect taxes.

-

Reform sequencing: Build consensus across provinces, civil society, and business before implementing.

-

Leverage advantages: Special economic zones in textiles, pharmaceuticals, and IT; diaspora engagement; and inclusive finance models.

-

Innovative financing: Explore sukuk and Islamic finance for infrastructure and renewable projects.

-

Governance first: Merit-based civil service, independent regulators, citizen oversight, and performance-linked public spending.

Above all, reforms must be anchored in domestic ownership and long-term commitment rather than external compulsion.

Conclusion: Choosing the Harder, Promising Road

Skeptics argue Pakistan’s instability makes reform impossible. Yet Vietnam, Bangladesh, and Ethiopia all began with severe obstacles—and transformed themselves. What they shared was not ideal conditions, but perseverance, pragmatism, and people-centered strategies.

Pakistan now faces a stark choice: continue cycling through IMF bailouts, or embark on deliberate, consensus-driven reforms. The latter path is harder but holds the promise of fiscal sovereignty, resilience, and a brighter future for millions.

Leave a Reply